Hamilton Hall

Opened in 1907, Hamilton Hall is the hub of Columbia College. With a statue of Alexander Hamilton situated in front of the building, Hamilton Hall celebrates the legacy of another Founding Father.

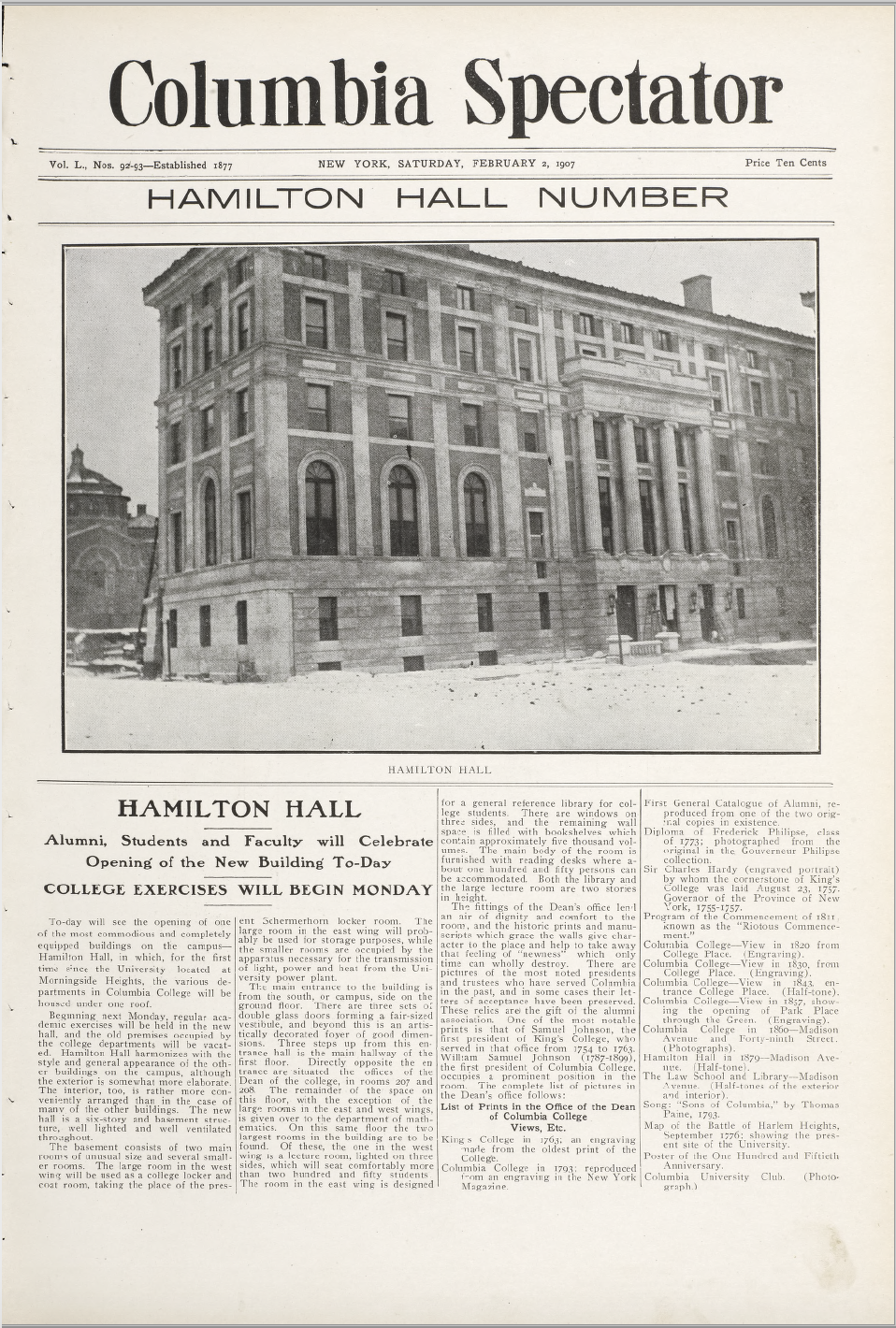

Special edition of The Spectator on Hamilton opening, February 2, 1907

Special edition of The Spectator on Hamilton opening, February 2, 1907

As an orphan in St. Croix, Hamilton was familiar with slavery in its most brutal form. He developed, at an early age, a strong distaste for the institution, as he later referred to slavery as a source of instability in the new republic as it interfered with America’s industrial and commercial progress. Hamilton, however, was much like his counterpart John Jay in his criticism of slavery; the affairs of a nascent nation, its developing ideologies, and his place in history trumped his anti-slavery conviction. Furthermore, Hamilton’s study on mainland U.S. was financed with money derived from slavery and—again, much like Jay—he married a member of a major slaveholding New York family. Like the other founders, he frequently embraced the language of metaphorical slavery when referring to the British control of America.

Despite his rejection of natural Black inferiority and his support for admitting Black soldiers into the Revolutionary Army, Hamilton’s priority lay with the project of creating a strong national government. The result was his silence toward the perceived injustice of slavery; Black people, as he saw it, did not come before the new nation’s unity—the white man’s unity.

Hamilton’s personal legacy is as complicated as that of the building. When Hamilton opened in 1907, it housed the Office of the Dean and seven academic departments of Columbia College, which were to be under one roof for the first time since the University moved to Morningside Heights. Among all administrators and professors who moved into the College’s new home in 1907—listed in the Spectator’s issue on Hamilton’s opening—one should be noted for his hidden notoriety.

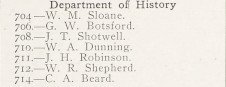

List of professors on the 7th floor of Hamilton, 1907 (Spectator)

List of professors on the 7th floor of Hamilton, 1907 (Spectator)

William Archibald Dunning was a professor of history and political theory at Columbia and had his office in Room 710 of Hamilton. Best known for inspiring a white-supremacist school of Reconstruction historiography called the Dunning School, the Columbia historian advocated for the return of a system paralleling slavery—also known as Jim Crow—for the peaceful coexistence between Black and white races in their most natural state—that of slave and master.

A Columbia professor who was a founder and president of the American Historical Association (AHA) and American Political Science Association (APSA), Dunning was also a student of Columbia. Although he was removed from Dartmouth College for participating in a violent mob attack, Dunning got his second chance at collegiate education from Columbia in 1877—an opportunity he did not waste. As an undergraduate, Dunning earned several scholarships and forged close relationships with his peers and instructors, namely his predecessor John W. Burgess—founder of the Columbia School of Political Science (CSPS), which would later become the current Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS). Thanks to Burgess, Dunning moved on to CSPS to earn his graduate degrees and attended the University of Berlin, where he adopted the philosophy of Social Darwinism and the Germanic practice of scientific research in history and political science.

Under Burgess, Dunning crystallized his views on history and politics. In this sense, Burgess is the de facto founder of the Dunning School, but Dunning’s influence cannot be understated. If Burgess supplied the backbone of historiographical and political philosophies of the Dunning School, Dunning provided the flesh that is its constituents. Revered for his approachability, Dunning attracted many Southern students to attend Columbia, many of whom became a part of the Dunning School and reflected the changing student body of the College and University in the early 20th century. Thus, the aforementioned instigator of the 1924 cross burning, John B. Rucker, can be understood as the effective product of Dunning—a northern scholar—“southernizing” the northern university.

Furthermore, Dunning influenced countless, for many of his students went on to teach across America. The Dunningite scholars—most of whom were Dunning’s students at Columbia—erased the national memory of Black oppression and slavery through the biased archival research that only illuminated the white-Southern perspective; their students, in turn, sustained the narratives created by Dunningites, pervading the academic sphere for the first half of the 1900s and permeating the public sphere in the latter half. Arguably, this chain of racist progression is still alive today in the form of white nationalism and institutional racism.

Dunning and his academic white-supremacy also inspired those who aimed to resist and re-write the Dunning School narratives. The earliest example of such historians would be W. E. B. Du Bois. In 1910, in front of Dunning and the AHA, Du Bois presented “Black Reconstruction and its Benefits”—what would later become his seminal Black Reconstruction. Dunning praised the text, probably because he was impressed by a Black man’s capacity to write well.

However, Dunning is not simply significant because he was a Columbia racist. He must be noted because his position and influence at Columbia allowed him to have an outsized influence over the scholarship and politics of his time and beyond.

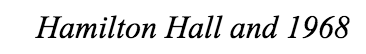

Dean of CC Henry Coleman speaking to student protesters during the SAS-SDS occupation of Hamilton Hall, April 23, 1968

Dean of CC Henry Coleman speaking to student protesters during the SAS-SDS occupation of Hamilton Hall, April 23, 1968

Apart from serving as the home base for Dunning at Columbia, Hamilton Hall was another epicenter of the 1968 protests, as it was one of the five buildings taken over by students and other activists in April, 1968.

The student protests at Columbia erupted after Columbia Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) activists discovered financial ties between the university and the Institute for Defense Analysis, a weapons research think tank backing American entanglement in the Vietnam War. Also addressed were the concerns of the Student Afro Society (SAS) in opposition to the construction of the Morningside gym. The protests by SAS and SDS garnered support and active participation from non-Columbia students and the surrounding Harlem community, resulting in the student occupation of many university buildings and their eventual forced removal by the New York City Police Department.

At first, a multiracial coalition of protesters occupied the Hamilton Hall lobby and held Columbia College Dean Henry S. Coleman hostage in his first-floor office. Black student activists, however, eventually asked the white protesters to exit the building in an effort by the SAS to establish independence from the SDS in its objectives and methods. The SAS, in essence, aimed to magnify and deter the University’s encroachment into Harlem’s public lands through disciplined, unmoving occupation of Hamilton, whereas the white students of SAS, as then SDS members recall, were “ragtag, messy, arguing constantly with each other.” The SAS also recognized the unique struggle for Black activists to contradict popular negative stereotypes tying Black protesters to property destruction; an exclusively SAS occupation in Hamilton allowed Black activists to avert potential conflicts with the SDS about destruction of University property.

Following the exodus of SDS protesters, the SAS declared Hamilton Hall as “Malcolm X Liberation College.” This timely declaration forced Columbia to confront the issue of race only eight days after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and in the midst of widespread rioting in the surrounding Harlem community.