Butler Library

Opened as South Hall in 1934, Butler Library celebrates the legacy of Nicholas Murray Butler, 12th and longest-reigning president of the University. Just as the Library is central to Columbia, Butler, too, was central to the University and its growth during his presidency.

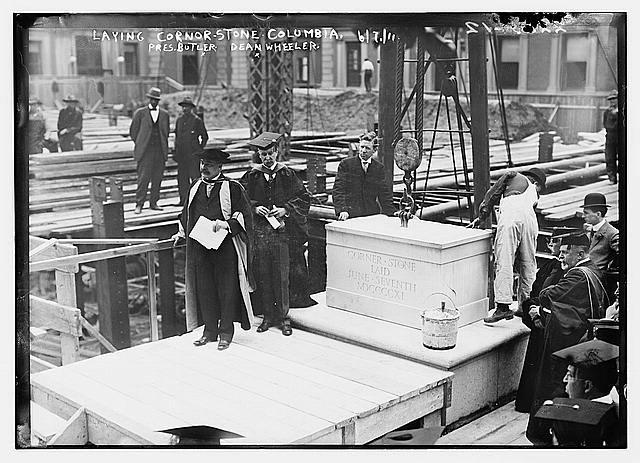

Butler laying cornerstone, June 7, 1911

Butler laying cornerstone, June 7, 1911

During his time as a student in Columbia College, Theodore Roosevelt affectionately called him “Nicholas Miraculous.” In some respects, Roosevelt was right. Butler’s influence on the University, domestic politics, and American higher education was “miraculous.”

Butler was a successful man in many respects. An active politician, he ran for the vice-presidency under Republican William H. Taft in the Election of 1912, which Democrat Woodrow Wilson won. Furthermore, Butler persuaded Andrew Carnegie to establish the Endowment for International Peace, which he served as head of the Endowment’s section on international education and communication. He served as president of the Endowment from 1925 to 1945, which landed him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

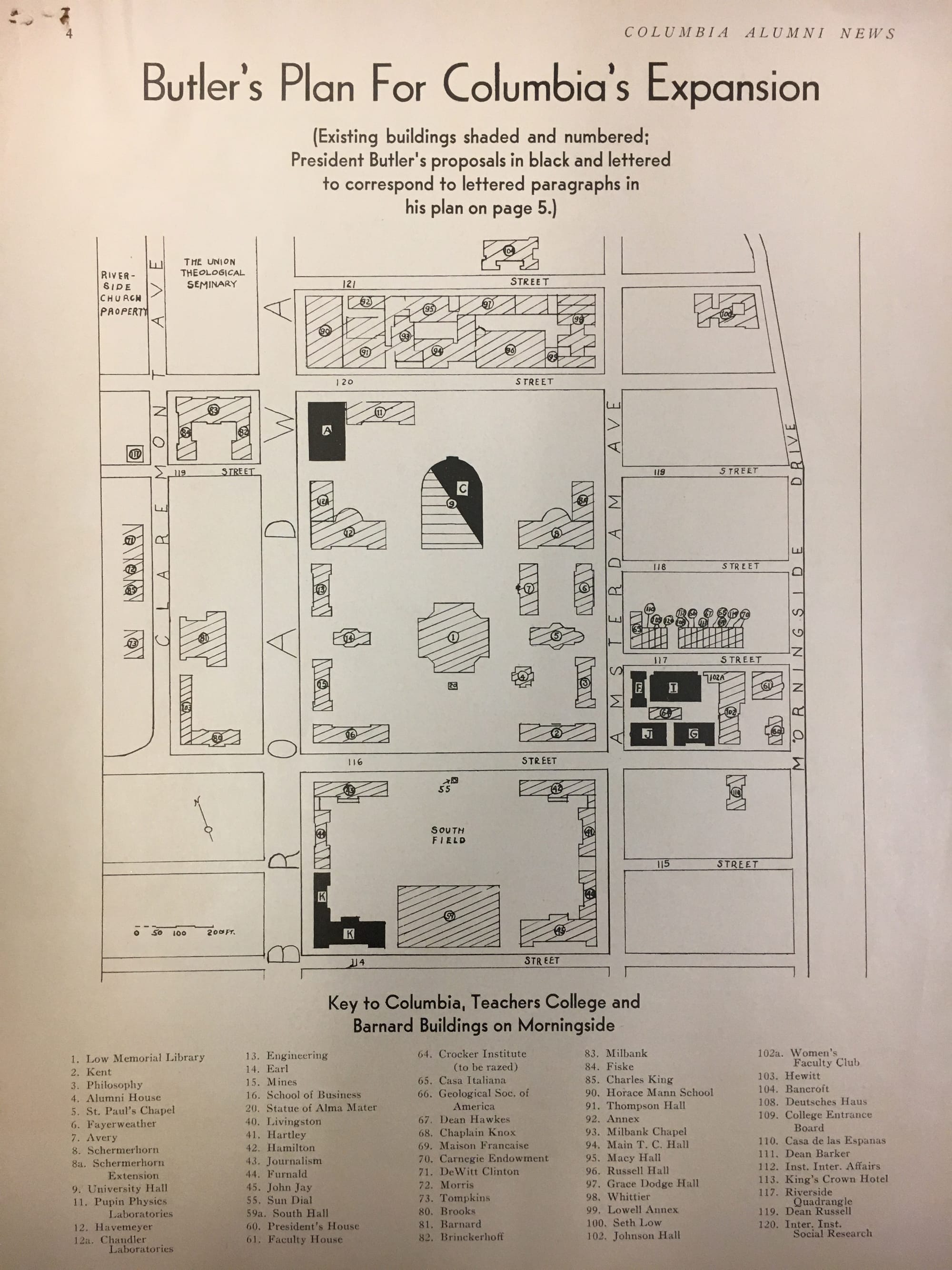

From Columbia Alumni News

From Columbia Alumni News Portrait of Nicholas M. Butler

Portrait of Nicholas M. Butler

At Columbia, Butler’s legacy entails the “University” of “Columbia University.” Under his presidency, Columbia witnessed exponential growth and joined the ranks of other major research universities like Harvard and Yale. Butler stepped into the University administration with well-established connections and knowledge of the workings of University politics; centralizing the power of the president, Butler ran Columbia with ambition that surpassed that of his predecessors.

In 1887, he founded an institute that later became Teachers’ College and new graduate schools emerged after he became acting president in 1901, such as the schools of journalism and dentistry. The student body increased from 4,000 to 34,000 and the faculty grew proportionally, owing to an increased professional salary and a growing endowment that attracted star professors in nearly every field of humanities.

Columbia expanded physically as well. Butler’s construction plan averaged a new building each year, including the creation of Hartley, Livingston, and John Jay Halls. The Morningside campus enlarged its position in the neighborhood and the University purchased real estate rapidly. Butler’s policy of expansion, however, eclipsed a much darker side of his presidency, his legacy of destruction.

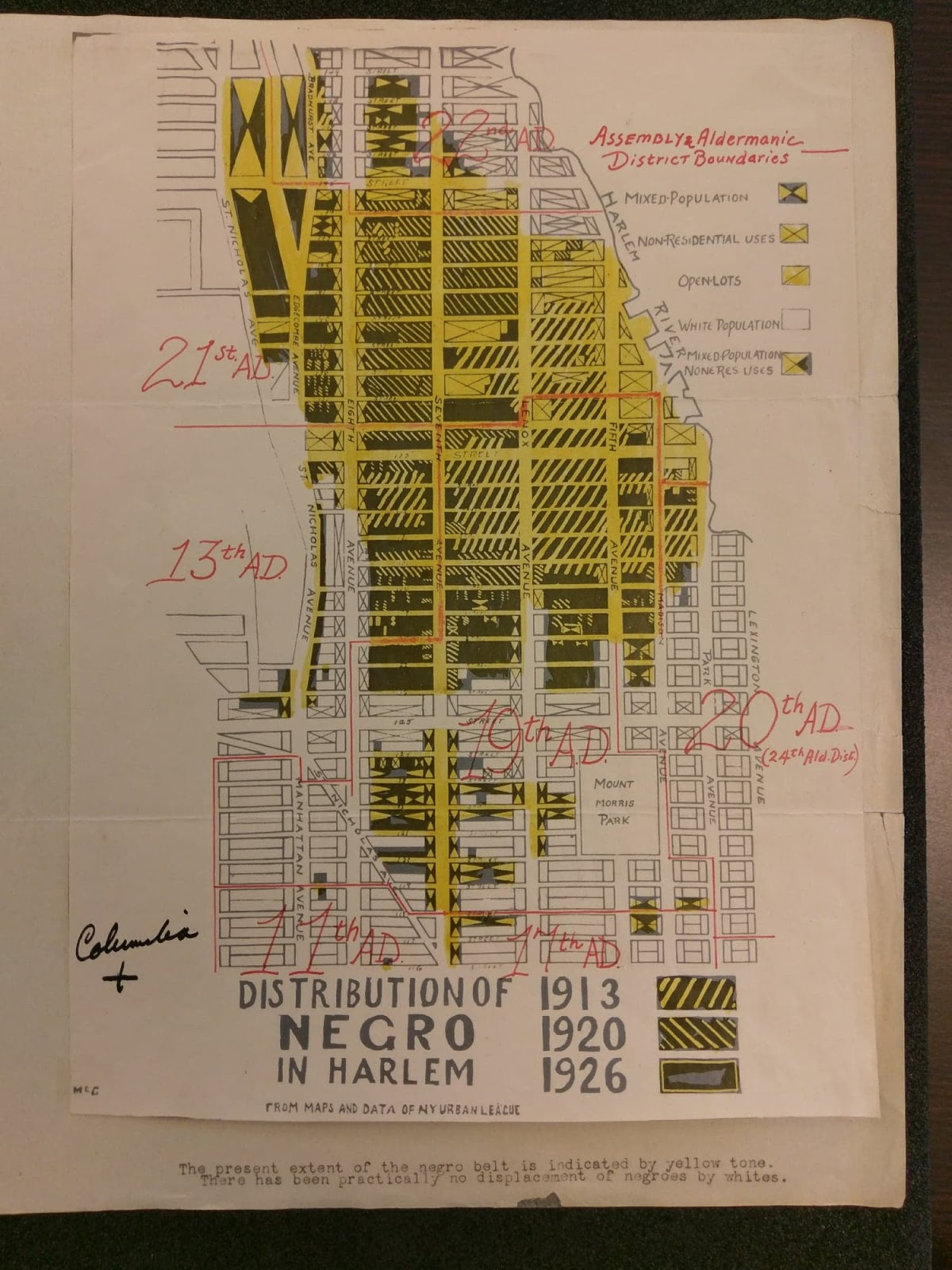

On November 30, 1926, John Jacob Coss, professor of philosophy and a founder of the Core Curriculum, wrote a letter to Butler that enclosed a map titled “Distribution of Negro in Harlem,” detailing the property of Black residents that Columbia should purchase and control. The letter and the map are the best archival sources in existence that highlight the dark side of Butler’s presidency: Columbia’s history of displacement in Harlem.

Lionized by Columbia College’s official website as “a model for two generations of staff,” Coss was the effective founder of the University’s famed Core Curriculum, specifically what is now called Contemporary Civilization. Coss’ profile on the website elucidates his legacy: “No Columbia faculty member had a greater influence on the course in Contemporary Civilization in its first decades than John J. Coss.”

Coss had an enormous impact on Columbia’s academics. Apart from the Core, he also served as the Director of the Columbia Summer Session and an administrative confidant to Butler during his presidency. Much of the existing correspondence between Coss and Butler pertain to the Summer Session, but the aforementioned letter offers direct evidence of the University’s role in displacing Black residents of Harlem.

Coss’ letter confirms long-suspected motives behind Columbia’s politics within Morningside Heights, as it reveals high-ranking University officials taking action against what they perceived as a threat to Columbia’s progress: a growing Black population.

Map in Coss' Letter titled, "Distribution of Negro in Harlem"

Map in Coss' Letter titled, "Distribution of Negro in Harlem"

Relevant Documents:

Manuscript of Letter, John J. Coss to N. M. Butler, Nov. 30, 1926.jpg